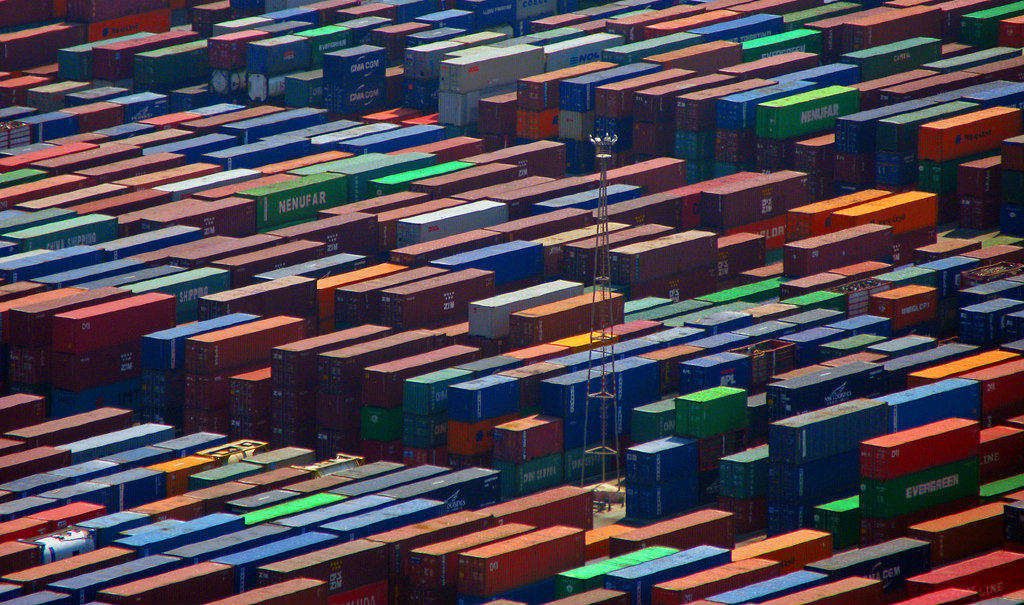

They spend their lives crossing the ocean, carrying bunches of bananas to Germany and fleets of cars to Colombia, swapping copper from Zambia for t-shirts from China. They may look like big dumb boxes, but they’re crucial cogs in the global economy. And when it’s time to retire, instead of heading to the scrapheap they’re playing a major part in some of today’s coolest urban development projects.

In just a few years, shipping container architecture—or ‘cargotecture’—has become one of the hottest trends in building. Strong, cheap and plentiful, disused containers are popping up as homes, schools, hotels and museums.

The latest big plan comes from Hong Kong architects OVA Studio. Their Hive-Inn City Farm would bring a modular high-rise farm to the middle of Manhattan. Individual units could be rented by restaurants to grow food and farm fish or small livestock. Some might be taken up by local residents as private gardens, while others would harvest energy and recycle water and waste to make the whole thing self-sustaining. OVA Studio’s founder and director Slimane Ouahes told PSFK that “it will bring back a bit of nature in our urbanised environments, cut down the food production chain, let people benefit from fresh food and also from being able to visit where the food is produced.”

The Hive-Inn City Farm would bring green space and local produce to the streets of New York

Like many a utopian urban concept, it will struggle to find the investment and planning permission necessary to ever get off the ground. But there are plenty of other disused containers out there already enjoying useful second careers.

One of the first major building projects to use them was Container City in London’s Trinity Buoy Wharf. The cluster of live/work spaces and artist studios was built using 80% recycled materials. Nearby in trendy Shoreditch, Boxpark plays host to a rotating cast of shops and restaurants, from global brands like Nike and Marimekko to the more local (and tormentingly delicious) Dumdums Donutterie. A similar project, Re:START — which, along with Boxpark, also claims the title of world’s first pop-up mall — has helped breathe life back into Christchurch’s earthquake-stricken central business district.

And it’s in that sort of community, where resources are scarce and development needs are urgent, that cargotecture is at its best. To bring safe drinking water, electricity, vaccinations and wifi to people who need them, Coca-Cola is deploying EKOCENTERs in distressed parts of the developing world. What it dubs ‘a downtown in a box’ is a 20-foot shipping container converted into a kiosk that houses a water purification system and community centre, delivering 800 litres of clean water every day at the hourly electricity cost of less than a standard hair dryer. These are run mainly by local female entrepreneurs and, as you’d expect, you can buy a Coke there too.

Because these projects make productive use of the huge number of shipping containers wasting away in our ports, they tend to have an eco-friendly air to them. But cargotecture can have its drawbacks, starting with the energy needed to make the boxes habitable. Between sandblasting to remove hazardous chemicals, moving them into place by crane and installing enough insulation and windows to make them comfortable, it can be cheaper and smarter to build from scratch with a traditional wood frame.

But with millions of containers in circulation, growing demand for affordable building materials, and smarter ways of making and remaking containers into useful structures, we’re likely to see a lot more of these settling down onshore.

Photo credit (Re:START): Nick Thompson